As a Christian community inspired and challenged by the radical social-justice mandates of both the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Testament, Emmanuel builds on its long history of social action.

Our centennial history tells the story of our fourth rector, Elwood Worcester (1904-1929), being told by a woman on Newbury Street, “I often see your people coming out of church and, oh, it is a beautiful congregation.” Worcester said he wished that “it was not quite so beautiful, but that it had a larger infusion of humbler persons and that Emmanuel represented more of all sorts and conditions of men.” Certainly Worcester with his Emmanuel Movement, which ministered to people with tuberculosis and alcoholics, helped to make Emmanuel a more diverse and inclusive place. Rector Al Kershaw (1963-1989) once issued a press release admonishing reporters not to refer to Emmanuel Church as “fashionable”.

Our parish historian Mary Chitty has delved into pew deeds, parish registers, and Google Books to learn more about early parishioners. She concludes that Emmanuel has always been more than just a parish of prominent movers and shakers in Boston, though it has been that as well.

Our Timeline of History @ Emmanuel offers more detail on these ministries:

- 1877: Cooperative Society of Volunteer Visitors to the Poor

- 1897: The Rev. Henrietta Godwin’s ministry to the poor

- 1905: Emmanuel Memorial House’s kindergarten, summer program for children & gymnasium for the mission parish of Church of the Ascension

- 1908: Chelsea Fire relief

- 1912: Free Legal Bureau

- 1918: Shelter for children made homeless by influenza epidemic

- 1970: Episcopal Women’s Caucus founded by Pauli Murray et al.

- 1986: Refugee Immigration Ministry founded by The Rev. Constance Hammond

- 1996: Ecclesia Ministries founded by The Rev. Deborah Little Wyman

Civil War Era

We have relatively little knowledge of the Civil War’s impact on the parish, which was founded by abolitionists in 1860, but several stained-glass windows and plaques remind us of those years. Some of the eight panels that make up the West Window speak to us of Boston abolitionists. The upper-middle panels were given in memory of Nathaniel Bowditch, who died in the Civil War. Given by William R Lawrence, it was designed by Nathaniel’s father, abolitionist and public-health pioneer Henry Ingersoll Bowditch, who at considerable professional and personal cost founded the Anti-Man Hunting League.

The right-bottom window was given in memory of merchant and philanthropist Amos Lawrence. The one to the left of it may be also connected with him, as he was father of founding member of Emmanuel, William R. Lawrence, whose brother Amos Adams Lawrence gave a pension to John Brown’s widow and was a key figure in the US abolition movement in the years leading up to the Civil War.

Into the 20th Century

Much of our information on work with people on the margins comes from church yearbooks published between 1883 and 1917. Much of the work was done in missions established in poorer neighborhoods. These properties became a financial burden and were given in 1937 to our diocese and the Catholic Church. Fifteen Newbury Street also housed a number of outreach activities.

The Dorcas Society was organized in 1861 to help poor women by giving out sewing. As reported in our yearbooks, this group was still active in the early 20th century. In the winter of 1905-1906, over a hundred old, needy, and infirm women received work. Our Music Room has a small bronze plaque honoring Miss Waters, a long-time secretary of the Dorcas Society.

Mothers’ meetings, organized in 1902 at Emmanuel, were held Thursday afternoons from November to May, as well as at its mission Church of the Ascension. In 1906, they averaged 40 attendees, and programs included talks by two nurses from Children’s Hospital. “Although the women were very industrious, it was regarded by many as a party, the one pleasure in a busy week.”

In its 1908 yearbook report this group had 100 members with attendance averaging 50-60. The mission was described as “work and play” as “perhaps because work is their habit of life our mothers seem to prefer work to play.” Activities included sewing for summer camp Fay Cottage and making “sheets, aprons and flannel underwear, which we sold at cost to mothers who were unable for lack of time to sew for themselves and their little ones.” The Christmas party included a tree, remembrances for everyone, a magician and plenty of ice cream and cake. This was “the gift of one good friend who enjoys making these women of many cares forget them for a little while in real Christmas mirth.” With “the stamp-saving system…many of the women have saved against a rainy day a little money.”

The 1911 yearbook described the mission as “to give a pleasant afternoon to a group of women who have the same social instincts as their sisters in other walks of life, but without the means for gratifying it. Their habit of life is to work, and so they sew industriously while they visit in groups or listen to a bright story” or music. The Women’s Missionary Society sent boxes to historically black colleges: St. Paul’s, Lawrenceville VA, St. Augustine’s, Raleigh NC, and St. Mary’s School [for Indian girls] in Rosebud SD. The missal stand in our chancel was a gift from St. Augustine’s in 1899. The Guild was organized in 1878 and served Miss Burnap’s Home for Aged Women, Sailor’s Haven, sick sailors in Chelsea, and “poor whites”. Summer work at Fay Cottage in Falmouth gave 149 people aged from 4 weeks to 80 years ten days respite from work and care. There were summer excursions to Bass Point, Nahant, for about 900 people.

Emmanuel Movement

People with tuberculosis and alcoholics certainly qualified as being on the margins in the early 20th century. Jim Sabin’s ”Shared medical appointments” posted to the Health Care Organizational Ethics blog says:

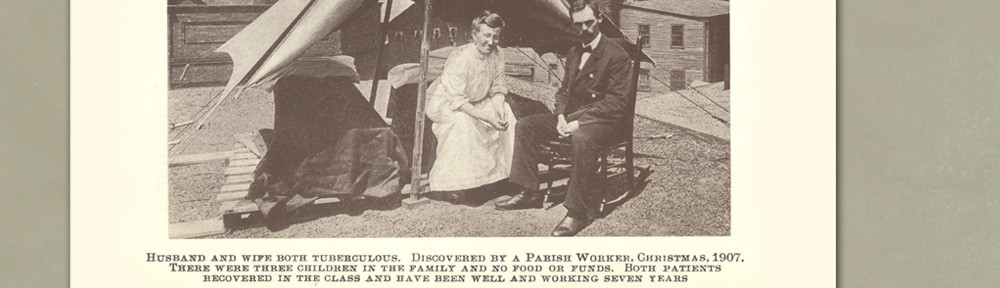

In 1905 Dr. Joseph Hersey Pratt, then at the Massachusetts General Hospital and later at the New England Medical Center, began to hold what he called the “tuberculosis class” at the Emmanuel Church in Boston. Pratt thought of the class as an efficient way of encouraging patients to follow a rigidly defined regimen of out-of-doors rest, the only treatment for TB at the time. Patients were directed to spend day and night in tents erected on the roofs and balconies of Boston tenements. A “friendly visitor,” the prototype of the medical social worker – made regular visits to the home to provide supervision and support, and to assist the family in making the needed practical arrangements. A subsidy provided by Dr. Elwood Worcester, rector of the Emmanuel Church, paid the salary of the friendly visitor and aided in purchasing tents, blankets and other necessities. Pratt ran the class for 18 years. His results with poor patients from Boston appeared to be similar to the results achieved at the best sanataria.

Native Americans

Mary Burnham, a parishioner at Emmanuel, founded a society for the support of Episcopal missions to the Indians in 1863, later called The Dakota League. K.B. Kueteman in “He Goes First: The Story of Episcopal Saint David Pendleton Oakerhater” noted:

Mary Douglass Burnham, born in Quincy, Massachusetts on May 13, 1832, the oldest of nine children … was no stranger to the American Indian. In 1863, at Emmanuel Church in Boston, she founded a society for the support of Episcopal missions to the Indians. This society was later called The Dakota League. In February of 1878, Deaconess Burnham, while visiting her brother Henry and his family in St. Augustine, Florida, made the acquaintance of Pratt, and was introduced to the Indian prisoners at Fort Marion. Learning of Pratt’s intentions to bring about the further education of as many of the prisoners as desired such an education, Burnham began in earnest to arrange for some of the prisoners to return with her to the east to study for the ministry.